I just spent a week in St. Agnes in a smallish cottage in Rosemundy with my mum and nearly 2 year old daughter. I went to get away from the falling down ceiling in the bedroom which builders had arrived to stick back up and my mum so she could have a very much needed half term break.

It was a tough week. Not only was it really freezing cold and wet, but Winni my daughter was ill more or less the whole time. Apart from being scary at times; her coughing through the night, temperature rises and her general lethargy it also affected her behaviour towards me and my mum. She became super clingy to me and if I looked away for a moment or tried to have a conversation she would raise a small hand and say 'hit!' towards my mum. If not hit then it would be a whispered 'kick!'. Fortunately, my mum didn't take it personally but by the end of the week even she was finding it slightly unnerving. This was odd and tiring. She is back to her cheerful self, my daughter that is - still with snotty nose but then I think that's here to stay at least until summer.

In the midst of illness we did make it to two table top sales and I went to a jumble sale in the Scouts Hut. What a great idea to have a jumble sale on a Friday evening! There wasn't much stuff to be had and anyway I am not as good as I once was at spotting it! I used to go to jumbles every Saturday religiously. Especially as a kid with my mum and then again when I was at University and trying to support myself with a stall at Camden Market. Jumble sales and charity shops were a necessity. In those days coming home with a black sack brimming over with 5p purchases was the norm.

I went to a jumble sale first one in ages a couple of weeks ago with my friend Jo in a village just outside Brighton called Ditchling. It was £1 to get in and then everything was 50p. I thought this was a bit much but then we did get some good bits and pieces. I had glimmers of the old excitement and nerves standing in the queue and watching it grow slowly as the minutes ticked by. Sussing out the potential competition and making judgements about what people nearer the front of the queue might be going for. In the early days I was very single minded. I knew what to look for and in what order to sweep the stalls. I could spot an interesting fabric from across the room. Also, if you had made the decision that people ahead of you were not dealers then the whole thing was quite leisurely however, if there were others with 'an eye' then it all became a much more extreme sport.

We went to The Tate in St.Ives, the Eden Project, and the Lost Gardens of Heligan (although we didn't actually go in - it would have been £8.50 each and really Winni was not at all up to it. We had the good fortune of asking a gardener what there was to see and he said not a lot at this time of the year). I managed to get a wheel clamp in St. Ives and even my spontaneous bursting into distraught teariness were not enough to appeal to the human beingness in the humourless man who silently took £74 off me. I did ask him if, human being to human being there was any way he could let up with this clamping? He was not a human being and could not be appealed to! It did cross my mind to beg as possibly my only real chance of getting any sympathy - but I just could not bring myself to. I had left Winni and my mum down by the harbour eating chips. When I finally got back to pick them up in the van we all got so caught up in my rage against the inhumanity of the car park mafia that I drove off and left the buggy in the middle of the road!

Rosemundy, is a two way street. St. Agnes is incredibly well connected by bus to all areas and Rosemundy is very much on the bus route (as we found out!) even though it's really steep and cars park in what turns out to be a particularly key spot on the hill. Every other bus that charges up this little lane is foiled by the row of cars parked on the right half way up. I went out one evening to have a look.

Mum and I had got a little freaked out by the passengers on the lower deck staring at us in our sitting room and those on top into our bedroom. The bus had come to a halt because it couldn't get through the narrow gap left by the parked cars. The driver called the depot to let them know. Everyone on the bus got more and more grumpy. Soon, the passengers abandoned their travelling plans and got off the bus. Then the bus driver starts to reverse down the hill to find an alternative route. Not an easy thing to do. I really wanted to have a conversation with someone about how this tiny little road ever came to be a carrier of buses - both ways. At least make it one way! Maybe I should speak to the owner of the cottage about getting some more heavy duty nets curtains and triple double glazing?

Wednesday 24 February 2010

Wednesday 10 February 2010

10 minutes

I have an interview tomorrow afternoon at Goldsmiths for an MA in Art Psychotherapy. I have 10 minutes to present myself as a practicing artist with a portfolio of artwork as part of a group interview! My wonderful friend Jo spent Friday evening with me. We drank sparkling wine (my first drop of alcohol in 40 days – well almost) and we went through all my art work and together we worked out something about the journey that I have been on over the last few years - and here it is...

I did an O and A level in art. I think I got an A for the former and a B for the latter. I didn't go to art school at 19 although I might have done but instead I headed for Sussex to do Social Anthropology which not only sounded fantastic (I had never heard of it as a subject before then) but meant that I wouldn't be following in my mum or dad's footsteps. They would know nothing (for once) about what I was learning. Some years later after doing many many averagely interesting evening classes I decided to go for an Art Foundation. Two years part time and just down the road at City College. I wanted the opportunity to apply myself and make a commitment to my art.

I spent two years taking my art and myself seriously (!) and decided to make it all about developing and honing my drawing and painting skills. Using pencil, charcoal, paint and ink I explored form and the line using my body as my subject. Only because it was there and I could access it easily. I was not at this point thinking in terms of my drawing having any actual relationship to me as the subject. I was looking at artists like Lucian Freud, Stanley Spencer, Euan Uglow and marvelling at their skill.

Then I discovered Jenny Saville and was totally blown away. Her work made me really want to paint and think about form. She works a lot from photos. Learning this, I took permission from her, which I now realise I had been doing all along without being aware of it. I started working from photos taken of different parts of my body, then drawing from them. My exploration of self in sketchbooks began with lots of looking and working stuff out.

Around this time I found out I was pregnant. I decided to continue with the course without really knowing how it would work out and started a fantastic sculpture class in the hope of taking my figurative work further. Every week I drove across country for 40 minutes to get to Partridge Green and work in a drafty studio with a small group at the sussex sculpture studios. Working from the figure in clay was really powerful. But almost more exciting was drawing from the contorted body (what was left of my beautiful sculpture) that I pulled from the mould. It was more interesting somehow than my sculpture – mirroring perhaps how I was feeling about my changing pregnant body.

About the same time I went to see Louise Bourgeois at the Tate. I marvelled at her fantastic little figures made from fabric found about her own home. Mother and child images – disturbing and beautiful. I decided that I too could use my life and pregnancy as the subject of my own art. It was time to confront my self censorship so I started looking at images of mother and child and motherhood in art; Henry Moore, Mary Kelly, Frida Khalo. Having found Tracey Emin's work annoyingly self referential and self absorbed - I realised that actually I was doing the same without really owning it.

At the same time as my body was changing we started to prepare our flat by ripping out the kitchen to make a space for a baby room. This meant unexpectedly that I got to have a little studio – the domestic space started to become really important. I could have several pieces of work on the go at the same time. Using paint I started looking at space, lines and the structure of the kitchen which was being built. I was dwelling on the external (home) and internal (pregnancy) space.

Once the baby arrived I went home to my mums in Suffolk where I grew up. I needed some familiar space and to get away from the chaos at home. I took lots of photos around the garden of the barn which I started working from in paint and charcoal. Finding the line and drawing back into the image. I really enjoyed working from these images that mean so much to me. I started to have 'feelings' while I was painting. This hadn't happened before – not quite like that!

Trying to find a focus for my final major project, in my 'studio space' I was exploring figures and self portraits again. This time it was an inter-generational theme – my mum and the baby, my dad and the baby – me. Even tho they won't meet, I was thinking - my mum and dad could be linked perhaps, through my paintings and through my baby. It's a bit nostalgic, but I was using my skills and trying to bring all of what I had learnt together.

An abstract figurative painting and an explosion of expression. I finally realised that my work had to be about what I am going through – a major life experience – why avoid it when it's such a huge life changing event. Embrace it I think. Also, as much as I enjoyed making the self portraits they just weren't very dynamic.

Making a large scale painting about the death of me and the beginning of motherhood based on photos Mike took in the Pompidiou – I look at line, colour, tone, space, figure, identity – everything goes in! The baby in the painting staring out beneath a very vivid and colourful blanket is the same baby that watches me from her pram as I paint. The whole process enables me to manage my transition into motherhood – I have more than one major project to work on and that suits me very well.

I have spent a few months looking at art and thinking. Anish Kapoor over the summer in Brighton, Pop Life at the Tate; Emin and Lucas in particular, Turner, Turner Prize, Saatchi Gallery and the Abstract America exhibition. Looking at other people's art gives me inspiration and motivation. I notice what I do and don't like. In the Saatchi gallery – one room literally drains the energy right out of me. I don't like the work in the room and it's exhausting just sharing space with it. I look more and read more about Tracey Emin and start to really admire her bravery. I am thinking about hidden realities and truths, the mundanity, the every day and about domesticity.

I have started an experimental drawing phase. I am drawing figures fast and furiously and it's not about skill now but about movement and expression about space behind and about the line. It's free – it's more abstract. Drawing in charcoal from moving images projected on the wall is so difficult and so incredibly great.

I am ready to begin and take confidence. To be emotive. I have worked out some very important stuff preparing for the interview. I have been on a major journey and I am in it for the long hall. All my thinking and feeling has to go into my work. I am ready to bring the thoughts and visuals to together – the body and the mind – and see what happens??

The body and mind hold the emotion – the unseen – hidden truths – the tension between containment and overflow, hiding and holding it all together. I see a body bursting at the seams – with ideas and excitement, tied up with brown string – and that's how I feel right now.

I will hear back from Goldsmiths about the interview in a few weeks time. I think it went quite well.

I did an O and A level in art. I think I got an A for the former and a B for the latter. I didn't go to art school at 19 although I might have done but instead I headed for Sussex to do Social Anthropology which not only sounded fantastic (I had never heard of it as a subject before then) but meant that I wouldn't be following in my mum or dad's footsteps. They would know nothing (for once) about what I was learning. Some years later after doing many many averagely interesting evening classes I decided to go for an Art Foundation. Two years part time and just down the road at City College. I wanted the opportunity to apply myself and make a commitment to my art.

I spent two years taking my art and myself seriously (!) and decided to make it all about developing and honing my drawing and painting skills. Using pencil, charcoal, paint and ink I explored form and the line using my body as my subject. Only because it was there and I could access it easily. I was not at this point thinking in terms of my drawing having any actual relationship to me as the subject. I was looking at artists like Lucian Freud, Stanley Spencer, Euan Uglow and marvelling at their skill.

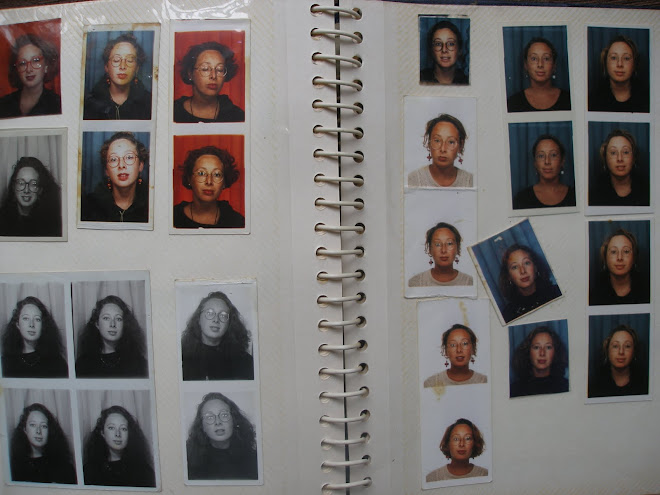

Then I discovered Jenny Saville and was totally blown away. Her work made me really want to paint and think about form. She works a lot from photos. Learning this, I took permission from her, which I now realise I had been doing all along without being aware of it. I started working from photos taken of different parts of my body, then drawing from them. My exploration of self in sketchbooks began with lots of looking and working stuff out.

Around this time I found out I was pregnant. I decided to continue with the course without really knowing how it would work out and started a fantastic sculpture class in the hope of taking my figurative work further. Every week I drove across country for 40 minutes to get to Partridge Green and work in a drafty studio with a small group at the sussex sculpture studios. Working from the figure in clay was really powerful. But almost more exciting was drawing from the contorted body (what was left of my beautiful sculpture) that I pulled from the mould. It was more interesting somehow than my sculpture – mirroring perhaps how I was feeling about my changing pregnant body.

About the same time I went to see Louise Bourgeois at the Tate. I marvelled at her fantastic little figures made from fabric found about her own home. Mother and child images – disturbing and beautiful. I decided that I too could use my life and pregnancy as the subject of my own art. It was time to confront my self censorship so I started looking at images of mother and child and motherhood in art; Henry Moore, Mary Kelly, Frida Khalo. Having found Tracey Emin's work annoyingly self referential and self absorbed - I realised that actually I was doing the same without really owning it.

At the same time as my body was changing we started to prepare our flat by ripping out the kitchen to make a space for a baby room. This meant unexpectedly that I got to have a little studio – the domestic space started to become really important. I could have several pieces of work on the go at the same time. Using paint I started looking at space, lines and the structure of the kitchen which was being built. I was dwelling on the external (home) and internal (pregnancy) space.

Once the baby arrived I went home to my mums in Suffolk where I grew up. I needed some familiar space and to get away from the chaos at home. I took lots of photos around the garden of the barn which I started working from in paint and charcoal. Finding the line and drawing back into the image. I really enjoyed working from these images that mean so much to me. I started to have 'feelings' while I was painting. This hadn't happened before – not quite like that!

Trying to find a focus for my final major project, in my 'studio space' I was exploring figures and self portraits again. This time it was an inter-generational theme – my mum and the baby, my dad and the baby – me. Even tho they won't meet, I was thinking - my mum and dad could be linked perhaps, through my paintings and through my baby. It's a bit nostalgic, but I was using my skills and trying to bring all of what I had learnt together.

An abstract figurative painting and an explosion of expression. I finally realised that my work had to be about what I am going through – a major life experience – why avoid it when it's such a huge life changing event. Embrace it I think. Also, as much as I enjoyed making the self portraits they just weren't very dynamic.

Making a large scale painting about the death of me and the beginning of motherhood based on photos Mike took in the Pompidiou – I look at line, colour, tone, space, figure, identity – everything goes in! The baby in the painting staring out beneath a very vivid and colourful blanket is the same baby that watches me from her pram as I paint. The whole process enables me to manage my transition into motherhood – I have more than one major project to work on and that suits me very well.

I have spent a few months looking at art and thinking. Anish Kapoor over the summer in Brighton, Pop Life at the Tate; Emin and Lucas in particular, Turner, Turner Prize, Saatchi Gallery and the Abstract America exhibition. Looking at other people's art gives me inspiration and motivation. I notice what I do and don't like. In the Saatchi gallery – one room literally drains the energy right out of me. I don't like the work in the room and it's exhausting just sharing space with it. I look more and read more about Tracey Emin and start to really admire her bravery. I am thinking about hidden realities and truths, the mundanity, the every day and about domesticity.

I have started an experimental drawing phase. I am drawing figures fast and furiously and it's not about skill now but about movement and expression about space behind and about the line. It's free – it's more abstract. Drawing in charcoal from moving images projected on the wall is so difficult and so incredibly great.

I am ready to begin and take confidence. To be emotive. I have worked out some very important stuff preparing for the interview. I have been on a major journey and I am in it for the long hall. All my thinking and feeling has to go into my work. I am ready to bring the thoughts and visuals to together – the body and the mind – and see what happens??

The body and mind hold the emotion – the unseen – hidden truths – the tension between containment and overflow, hiding and holding it all together. I see a body bursting at the seams – with ideas and excitement, tied up with brown string – and that's how I feel right now.

I will hear back from Goldsmiths about the interview in a few weeks time. I think it went quite well.

Pots of Liquid Flesh

It was a Friday evening. Mike and Bill were playing chess and I was surfing the internet searching for images of Lucian Freud’s paintings. Suddenly I stumbled across a painting by Jenny Saville, and the hairs on the back of my neck stood up. Excitedly I encouraged my companions to leave their chessboard for a moment and share in my discovery…

Jenny Saville grew up in Cambridge. She studied painting and drawing at Glasgow School of Art from 1989, catching the end of eleven years of Thatcherism. Unemployment was officially nearly 3 million, the unpopularity of the new poll tax charge had led to riots in London and as far as Thatcher was concerned, there was no such thing as society. On April 10th 1992, the year of Saville’s graduation, John Major led the Conservatives into power for a fourth term in office contrary to expectations.

Thatcher’s legacy was powerful, pervasive and left a significant impression on the young artists in the late 80’s and early 90’s. She had successfully appealed to the lowest common denominator and relieved us of any social conscience. The resulting mediocre, banal, mass consumer culture was accompanied by a raw, edgy selfishness and a widening gap between the have’s and have not’s. The yuppy - me first society was born, with a mindless pursuit of wealth and a tremendous growth in the art market.

The generation of artists emerging from the art schools in the late 1980’s (as Saville was just beginning) were known as Young British Artists (YBAs). Government funding cuts had left art schools struggling to survive. Students and teachers were making work that reflected their experiences of what was happening in Britain and their reactions to Thatcherism. Goldsmith’s College was at the forefront of major changes in art schools across the country. Abolishing the traditional divisions between the painting, sculpture and photography departments, lecturers inculcated a belief in their students that from day one they were artists.

The students from Goldsmiths – who became the YBA’s - were self confident, worked together to promote themselves and challenged what they saw as the complacency of the establishment. They used found objects, quotations and deconstruction to make art that represented themselves and their relationship to society. They also aimed to actively engage the spectator in the experience of looking as Saville would do later in her own work.

In 1997, Saville took part in the controversial Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art, alongside fellow YBA’s; Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Gary Hume, Jake and Dinos Chapman and Chris Ofili. The press had a field day with the, “raw humour, nastiness, inventiveness, obscenity, aggression, beauty, insouciance and failures of the work.” The Daily Mail rechristened the museum “The Royal Academy of Porn”.

“Not since the 60’s, when David Hockney bleached his hair, donned a gold lame jacket and became a painter-celebrity, has the London art scene generated so much interest,” wrote a journalist in 1999 describing Sensation as “the defining contemporary art collection of a nation”. With the YBAs, London became a centre of the international art world, a source of export to the New York art scene and a magnet for New York gallery owners.

I went to the Sensation Exhibition in 1997 and can remember the shark in formaldehyde, Mueck’s 'Dead Dad', and 'Myra' by Marcus Harvey, but I don’t remember Saville which, perhaps, says something about the hype at the time. While Saville was one of the YBA’s, albeit two or three year’s younger than Damian Hirst et al. her work seems to be less well known probably because it was less controversial and possibly because she is a painter and her subject the female nude.

Saville grew up looking at Freud, Bacon and Auberach. She was drawn to artists that depict the body like Velasquez and Courbet. De Kooning she describes as her ‘main man’ whose work she feels, pushes the medium of paint.8 She has often been compared to Freud but is closer to Bacon and de Kooning in her own opinion. Pondering her comparison to Freud, Linda Nochlin argues that Saville is at heart a conceptual artist, whereas Freud is a traditional painter trying to look as though he has a concept.

At Glasgow, Saville found only one female painting tutor but she followed in the footsteps of Scottish painters like Stephan Campbell, Ken Currie, and Peter Howson, all of whom had the same tutor - Sandy Moffat.9 She learnt about feminism and its influences on art practice and was influenced by work of French feminists Luce Irigary and Julia Kristeva and the artist Cindy Sherman.

Feminist critiques of representation at the time were arguing that the image of ‘women’ was constructed by men through a male dominated media and shaped the way women saw themselves and how they experienced being a women.10 These ideas were reflected by female artists. Even as a child looking through art books, Saville realised there were no women artists and she started to wonder why not.

"Could I make a painting of a nude in my own voice?” she asked, “It's such a male-laden art, so historically weighted. The way women were depicted didn't feel like mine, too cute. I wasn't interested in admired or idealised beauty."

Saville uses masses of photographs to create her ‘monumental nudes’. Often they are photographs of herself or bits of her friend’s bodies. They are not self portraits as Saville has said herself in the Monograph interview with David Sylvester, “I use me all the time because it’s really reliable, you’re there all the time”. She also likes the idea of using herself because “it takes you into the work”. She talks about how women have so often been the subject-object and this has an important implication for her not wanting to be just the person ‘looking and examining’. Females, as she says, are used to being looked at and she wants to be able to do both; looking and being looked at.

She also works from photographs of bruises and other injuries from medical textbooks. All are used as reference. Finding out what causes a stretch mark from a medical book, for example, helps her understand how to paint them. She’s aware of the ‘snobbery’ against using photos when painting from life - but doesn’t care. Using photographs of fragments of the body is a pragmatic approach particularly given the sheer size of her paintings and her subject. She doesn’t paint while looking at the figure. Instead she will have a model for a day and take rolls of film of close ups. Then, climbing up and down scaffolding with the use of a grid and mirrors she embarks on her paintings.

She is really interested in painting areas of flesh rather than the female body as such. “It’s as if the paint tends to become the body… When I put the paint on in layers, it’s like adding layers of flesh. There are areas of thick flesh, where the paint becomes more dense”. She mixes up large quantities of different colours in maybe three hundred pots rather than working from a palette. She tries to paint in a sculptural way.

Nochlin, who famously asked first in 1970 and again in 1980, ‘Why have there been no great women artists?” is impressed with Saville’s ‘painterliness’ and thinks she is one of the most interesting and exciting painters of our time. She writes about her work, “although the surface and the grid both play an important role in Saville's formal language, both are melted down and sharpened up by the virtuoso yet oddly repulsive brushwork that marks her style”.

In what may be her most current interview in May 2005 Simon Shama asked Jenny Saville about the types of bodies she paints. Her answer to this question and her analysis seem more sophisticated than earlier interviews.

“I try to find bodies that manifest in their flesh something of our contemporary age…I don’t paint portraits in a traditional sense at all. If they are portraits, they are portraits of an idea or a sensation”.

While living in New York, Saville observed the work of a plastic surgeon, Dr. Barry Martin Weintraub. She took photos of the operations and became interested in the ‘manipulations’ that could be made to the body. Importantly for her work she also gained insight into the psychological factors behind these changes to the body.

I stumbled across Jenny Saville’s work by accident. I was looking at images of Lucian Freud’s paintings, which I have been drawn to since I first saw them as a teenager, and found some images of Saville’s figures which really excited me. I was drawn to the images, without realising that the canvases were so huge. I find the fact she’s a female painter - inspiring. I read about her working from photographs which was a bit of a shock but also a relief. I had been trying to paint from the nude (using myself in the mirror) and felt I now had permission to explore working from photographs. This gave me something new to explore in my own work which felt liberating.

When I look at ‘Branded’, ‘Prop’, or ‘Propped’, all painted in 1992 or ‘Plan’ which is 9x7ft painted in 1993 and I mark out with a tape measure on my sitting room wall the dimensions and imagine sitting in front of the painting looking up at those images - I ask myself what these paintings are about. My head is full of the critiques I have read - some almost impossible to comprehend and a little intimidating. I see images that are strong and bold and by which I am humbled. I wonder if Saville gives us a female body – a nude – which makes us work. My eye darts across the paintings and I flick between the full paintings and the close up photographs to try and understand how the paint is applied to create these fleshy bodies. They are not easy on the eye and that is not their intention.

‘Plan’ draws me in, holds me transfixed and I crave to be able to stand in front of the real thing. These are unfamiliar images of the female body. Those available for public consumption (in newspapers, magazines and even in art) tend to be idealised images of a beautiful, thin female body. Saville’s bodies are ordinarily covered up or left indoors. Big breasts may be desirable but Saville’s breasts are huge colossal mammaries that are intimidating, hardly sexually alluring. These bodies do not lend themselves to voyeurism.

The naked body in ‘Plan’ is brave and bold. The towering figure looks down and demands your attention in a way that other common images of female bodies do not. I wonder whether these nudes are attractive to the male gaze and I think probably not. If her work critiques the young, alluring female body which has long belonged to the male painter/artist – I wonder if Saville’s naked bodies intend to confront or even repulse the average male viewer. They certainly don’t facilitate the normal consumption of the female form which, it could be argued, has been legitimated by a male aesthetic approach to figurative art. In this sense ‘Plan’ liberates the viewer and the figure depicted is liberated too.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)