It was a Friday evening. Mike and Bill were playing chess and I was surfing the internet searching for images of Lucian Freud’s paintings. Suddenly I stumbled across a painting by Jenny Saville, and the hairs on the back of my neck stood up. Excitedly I encouraged my companions to leave their chessboard for a moment and share in my discovery…

Jenny Saville grew up in Cambridge. She studied painting and drawing at Glasgow School of Art from 1989, catching the end of eleven years of Thatcherism. Unemployment was officially nearly 3 million, the unpopularity of the new poll tax charge had led to riots in London and as far as Thatcher was concerned, there was no such thing as society. On April 10th 1992, the year of Saville’s graduation, John Major led the Conservatives into power for a fourth term in office contrary to expectations.

Thatcher’s legacy was powerful, pervasive and left a significant impression on the young artists in the late 80’s and early 90’s. She had successfully appealed to the lowest common denominator and relieved us of any social conscience. The resulting mediocre, banal, mass consumer culture was accompanied by a raw, edgy selfishness and a widening gap between the have’s and have not’s. The yuppy - me first society was born, with a mindless pursuit of wealth and a tremendous growth in the art market.

The generation of artists emerging from the art schools in the late 1980’s (as Saville was just beginning) were known as Young British Artists (YBAs). Government funding cuts had left art schools struggling to survive. Students and teachers were making work that reflected their experiences of what was happening in Britain and their reactions to Thatcherism. Goldsmith’s College was at the forefront of major changes in art schools across the country. Abolishing the traditional divisions between the painting, sculpture and photography departments, lecturers inculcated a belief in their students that from day one they were artists.

The students from Goldsmiths – who became the YBA’s - were self confident, worked together to promote themselves and challenged what they saw as the complacency of the establishment. They used found objects, quotations and deconstruction to make art that represented themselves and their relationship to society. They also aimed to actively engage the spectator in the experience of looking as Saville would do later in her own work.

In 1997, Saville took part in the controversial Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art, alongside fellow YBA’s; Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Gary Hume, Jake and Dinos Chapman and Chris Ofili. The press had a field day with the, “raw humour, nastiness, inventiveness, obscenity, aggression, beauty, insouciance and failures of the work.” The Daily Mail rechristened the museum “The Royal Academy of Porn”.

“Not since the 60’s, when David Hockney bleached his hair, donned a gold lame jacket and became a painter-celebrity, has the London art scene generated so much interest,” wrote a journalist in 1999 describing Sensation as “the defining contemporary art collection of a nation”. With the YBAs, London became a centre of the international art world, a source of export to the New York art scene and a magnet for New York gallery owners.

I went to the Sensation Exhibition in 1997 and can remember the shark in formaldehyde, Mueck’s 'Dead Dad', and 'Myra' by Marcus Harvey, but I don’t remember Saville which, perhaps, says something about the hype at the time. While Saville was one of the YBA’s, albeit two or three year’s younger than Damian Hirst et al. her work seems to be less well known probably because it was less controversial and possibly because she is a painter and her subject the female nude.

Saville grew up looking at Freud, Bacon and Auberach. She was drawn to artists that depict the body like Velasquez and Courbet. De Kooning she describes as her ‘main man’ whose work she feels, pushes the medium of paint.8 She has often been compared to Freud but is closer to Bacon and de Kooning in her own opinion. Pondering her comparison to Freud, Linda Nochlin argues that Saville is at heart a conceptual artist, whereas Freud is a traditional painter trying to look as though he has a concept.

At Glasgow, Saville found only one female painting tutor but she followed in the footsteps of Scottish painters like Stephan Campbell, Ken Currie, and Peter Howson, all of whom had the same tutor - Sandy Moffat.9 She learnt about feminism and its influences on art practice and was influenced by work of French feminists Luce Irigary and Julia Kristeva and the artist Cindy Sherman.

Feminist critiques of representation at the time were arguing that the image of ‘women’ was constructed by men through a male dominated media and shaped the way women saw themselves and how they experienced being a women.10 These ideas were reflected by female artists. Even as a child looking through art books, Saville realised there were no women artists and she started to wonder why not.

"Could I make a painting of a nude in my own voice?” she asked, “It's such a male-laden art, so historically weighted. The way women were depicted didn't feel like mine, too cute. I wasn't interested in admired or idealised beauty."

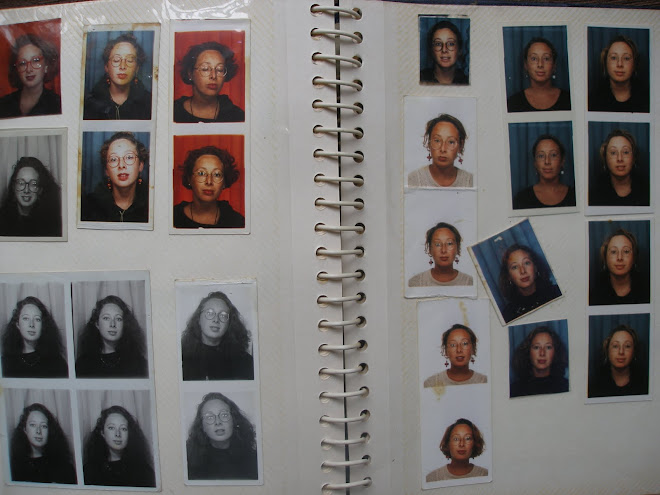

Saville uses masses of photographs to create her ‘monumental nudes’. Often they are photographs of herself or bits of her friend’s bodies. They are not self portraits as Saville has said herself in the Monograph interview with David Sylvester, “I use me all the time because it’s really reliable, you’re there all the time”. She also likes the idea of using herself because “it takes you into the work”. She talks about how women have so often been the subject-object and this has an important implication for her not wanting to be just the person ‘looking and examining’. Females, as she says, are used to being looked at and she wants to be able to do both; looking and being looked at.

She also works from photographs of bruises and other injuries from medical textbooks. All are used as reference. Finding out what causes a stretch mark from a medical book, for example, helps her understand how to paint them. She’s aware of the ‘snobbery’ against using photos when painting from life - but doesn’t care. Using photographs of fragments of the body is a pragmatic approach particularly given the sheer size of her paintings and her subject. She doesn’t paint while looking at the figure. Instead she will have a model for a day and take rolls of film of close ups. Then, climbing up and down scaffolding with the use of a grid and mirrors she embarks on her paintings.

She is really interested in painting areas of flesh rather than the female body as such. “It’s as if the paint tends to become the body… When I put the paint on in layers, it’s like adding layers of flesh. There are areas of thick flesh, where the paint becomes more dense”. She mixes up large quantities of different colours in maybe three hundred pots rather than working from a palette. She tries to paint in a sculptural way.

Nochlin, who famously asked first in 1970 and again in 1980, ‘Why have there been no great women artists?” is impressed with Saville’s ‘painterliness’ and thinks she is one of the most interesting and exciting painters of our time. She writes about her work, “although the surface and the grid both play an important role in Saville's formal language, both are melted down and sharpened up by the virtuoso yet oddly repulsive brushwork that marks her style”.

In what may be her most current interview in May 2005 Simon Shama asked Jenny Saville about the types of bodies she paints. Her answer to this question and her analysis seem more sophisticated than earlier interviews.

“I try to find bodies that manifest in their flesh something of our contemporary age…I don’t paint portraits in a traditional sense at all. If they are portraits, they are portraits of an idea or a sensation”.

While living in New York, Saville observed the work of a plastic surgeon, Dr. Barry Martin Weintraub. She took photos of the operations and became interested in the ‘manipulations’ that could be made to the body. Importantly for her work she also gained insight into the psychological factors behind these changes to the body.

I stumbled across Jenny Saville’s work by accident. I was looking at images of Lucian Freud’s paintings, which I have been drawn to since I first saw them as a teenager, and found some images of Saville’s figures which really excited me. I was drawn to the images, without realising that the canvases were so huge. I find the fact she’s a female painter - inspiring. I read about her working from photographs which was a bit of a shock but also a relief. I had been trying to paint from the nude (using myself in the mirror) and felt I now had permission to explore working from photographs. This gave me something new to explore in my own work which felt liberating.

When I look at ‘Branded’, ‘Prop’, or ‘Propped’, all painted in 1992 or ‘Plan’ which is 9x7ft painted in 1993 and I mark out with a tape measure on my sitting room wall the dimensions and imagine sitting in front of the painting looking up at those images - I ask myself what these paintings are about. My head is full of the critiques I have read - some almost impossible to comprehend and a little intimidating. I see images that are strong and bold and by which I am humbled. I wonder if Saville gives us a female body – a nude – which makes us work. My eye darts across the paintings and I flick between the full paintings and the close up photographs to try and understand how the paint is applied to create these fleshy bodies. They are not easy on the eye and that is not their intention.

‘Plan’ draws me in, holds me transfixed and I crave to be able to stand in front of the real thing. These are unfamiliar images of the female body. Those available for public consumption (in newspapers, magazines and even in art) tend to be idealised images of a beautiful, thin female body. Saville’s bodies are ordinarily covered up or left indoors. Big breasts may be desirable but Saville’s breasts are huge colossal mammaries that are intimidating, hardly sexually alluring. These bodies do not lend themselves to voyeurism.

The naked body in ‘Plan’ is brave and bold. The towering figure looks down and demands your attention in a way that other common images of female bodies do not. I wonder whether these nudes are attractive to the male gaze and I think probably not. If her work critiques the young, alluring female body which has long belonged to the male painter/artist – I wonder if Saville’s naked bodies intend to confront or even repulse the average male viewer. They certainly don’t facilitate the normal consumption of the female form which, it could be argued, has been legitimated by a male aesthetic approach to figurative art. In this sense ‘Plan’ liberates the viewer and the figure depicted is liberated too.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment